- Archaeology

More than a dozen mummies of kids with facial tattoos were found at an archaeological site in Christian-era Nubia.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

An artist's reconstruction of tattooing on the forehead of a 3-year-old girl from Kulubnarti.

(Image credit: Mary Nguyen/UMSL)

Share

Share by:

An artist's reconstruction of tattooing on the forehead of a 3-year-old girl from Kulubnarti.

(Image credit: Mary Nguyen/UMSL)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Kids as young as 18 months old were given facial tattoos in the Nile Valley region 1,400 years ago, archaeologists discovered while studying mummified bodies in Sudan. What's more, the practice coincided with the introduction of Christianity to the region known as Nubia.

"If the tattoos were a symbol of the wearer's Christian faith, then it might have been important for parents to create permanent ways to mark their children as Christian," study lead author Anne Austin, an archaeologist at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, told Live Science.

You may like-

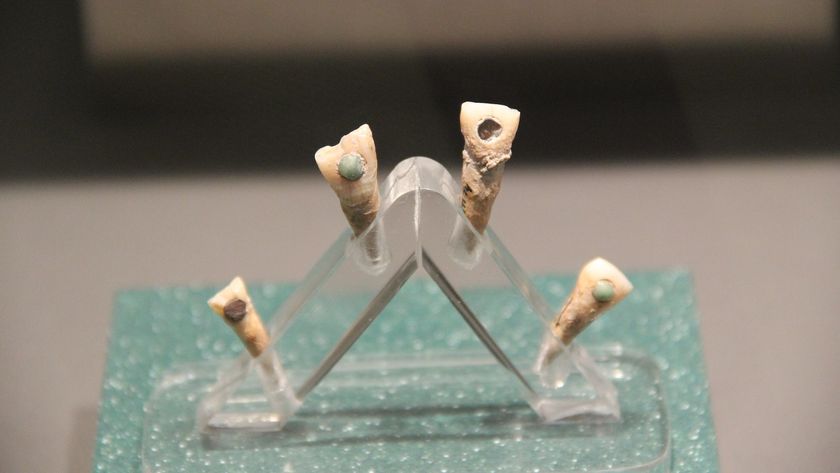

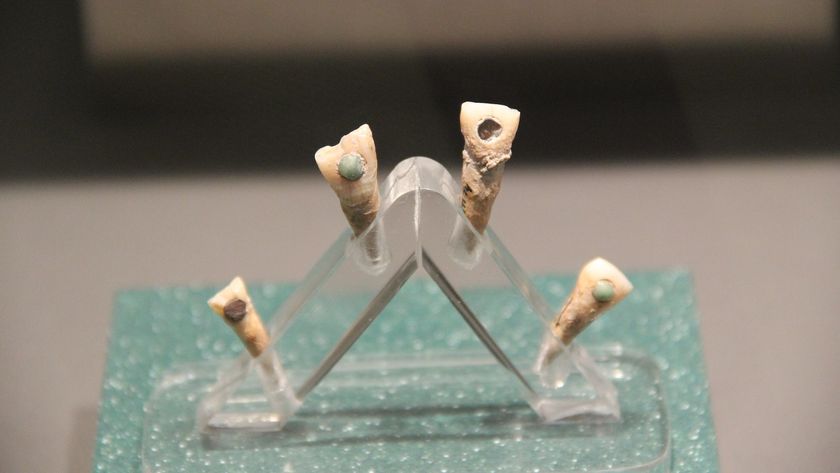

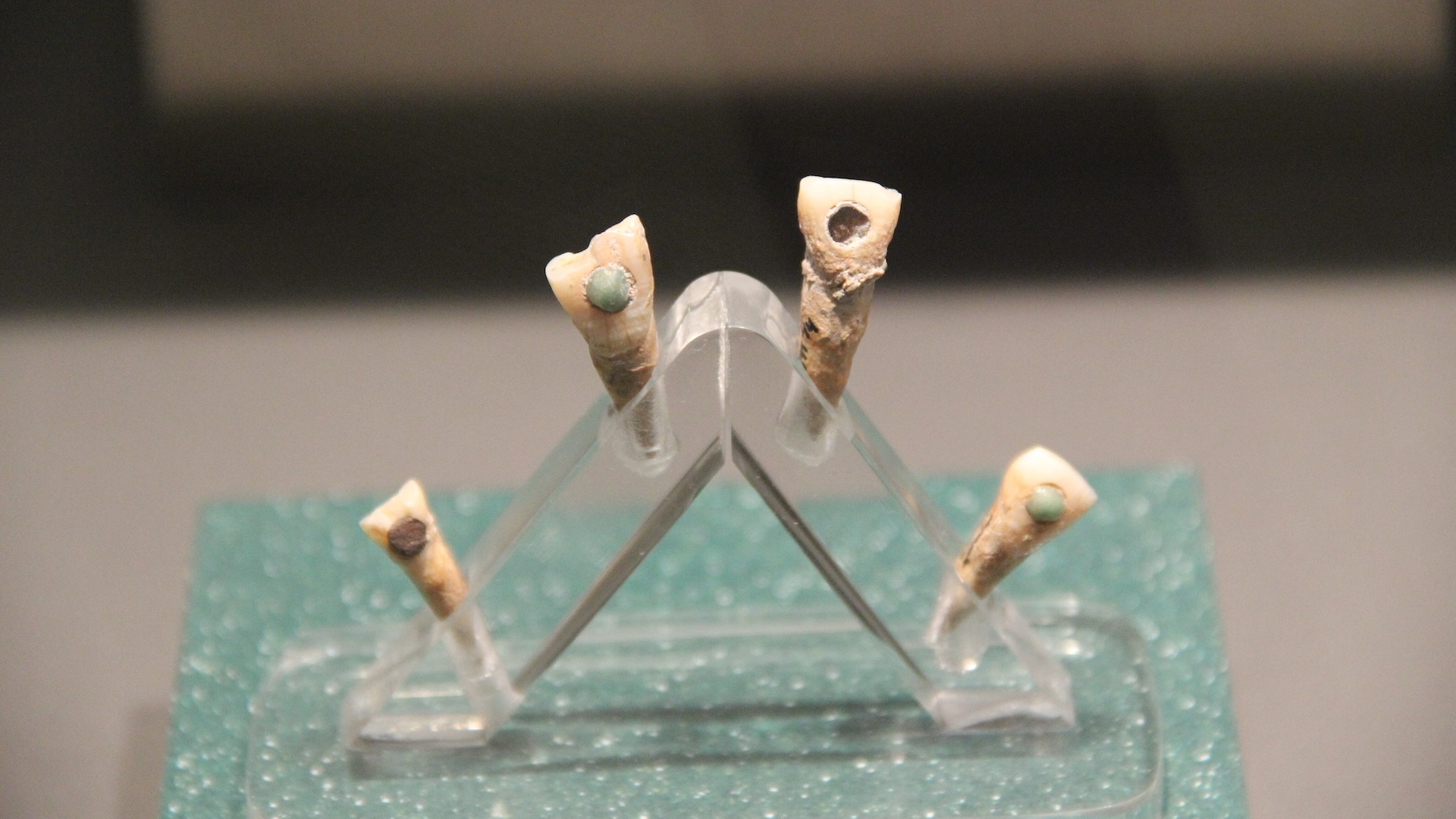

7-year-old Maya child had green jade 'tooth gem,' new study finds

7-year-old Maya child had green jade 'tooth gem,' new study finds

-

'We do not know of a similar case': 4,000-year-old burial in little-known African kingdom mystifies archaeologists

'We do not know of a similar case': 4,000-year-old burial in little-known African kingdom mystifies archaeologists

-

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

Tattooing is a long-standing human practice. Some of the oldest archaeological evidence of tattoos can be found on Ötzi the "Iceman," whose well-preserved 5,300-year-old body discovered in the Alps was decorated with 61 of them. Other early tattoos have been found on Egyptian mummies from 5,000 years ago, Siberian mummies from 2,300 years ago, and Peruvian mummies from 1,200 years ago. All of these examples were tattoos on adults, though; tattooed children are discovered much less commonly.

In the new study, the researchers identified extensive examples of tattooing at the Christian-era site of Kulubnarti in northern Sudan. Two cemeteries at the site were in use between A.D. 650 and 1000. Using microscopy with infrared lighting, which can penetrate skin to reveal tattoos barely visible to the naked eye, the researchers identified 17 people with definite tattoos and six people with possible faded tattoos.

While investigating exactly where on the body the people buried at Kulubnarti sported tattoos, the researchers noticed an unusual pattern: Two people had back tattoos, but the rest had designs on their foreheads, temples, cheeks or eyebrows. Facial tattoos are already relatively uncommon in the archaeological record, but the researchers found an even rarer practice: the tattooing of children.

Most of the Kulubnarti people with tattoos were children under age 11, the researchers wrote in the study, while the youngest person with definite tattoos was 18 months old. A 3-year-old girl was even found to have had one tattoo positioned directly over another tattoo, suggesting that young children were repeatedly tattooed.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.

The tattoos consisted of clustered dots and dashes. The most frequent design was four dots tattooed in a diamond pattern on the person's forehead, which could represent a Christian cross, according to Austin. "It's entirely plausible that tattooing was part of a form of baptism if it was used as a sign of Christianity at Kulubnarti," she said.

But the researchers are also investigating another theory for the widespread tattooing of children found in the cemetery.

"If parents tattooed their children in order to protect them or for medical reasons, then maybe the high rate of tattooing in young children shows us that people at Kulubnarti were facing unusually high amounts of health issues," Austin said.

You may like-

7-year-old Maya child had green jade 'tooth gem,' new study finds

7-year-old Maya child had green jade 'tooth gem,' new study finds

-

'We do not know of a similar case': 4,000-year-old burial in little-known African kingdom mystifies archaeologists

'We do not know of a similar case': 4,000-year-old burial in little-known African kingdom mystifies archaeologists

-

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

Forehead tattoos may represent parents' attempts to protect their kids from headaches or high fevers, both of which are commonly experienced in bouts of malaria, a disease with a long history in the Nile Valley, according to the study.

RELATED STORIES—'Christ' tattoo discovered on 1,300-year-old body in Sudan

—Lasers reveal hidden patterns in tattoos of 1,200-year-old Peru mummies

—Ötzi the Iceman used surprisingly modern technique for his tattoos 5,300 years ago, study suggests

The team also found that the Nubians likely used knives, not needles, to make the tattoos, based on the shape of the tattoo markings.

Even if the tattoos were simply decorative, Austin said, we should not be quick to judge past people for the practice.

"The form of tattooing at Kulubnarti — which could have been done fairly quickly — doesn't seem any more extreme than piercing a toddler's ears or circumcising newborn babies," she said.

Mummy quiz: Can you unwrap these ancient Egyptian mysteries?

TOPICS mummies Kristina KillgroveSocial Links NavigationStaff writer

Kristina KillgroveSocial Links NavigationStaff writerKristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Read more 7-year-old Maya child had green jade 'tooth gem,' new study finds

7-year-old Maya child had green jade 'tooth gem,' new study finds

'We do not know of a similar case': 4,000-year-old burial in little-known African kingdom mystifies archaeologists

'We do not know of a similar case': 4,000-year-old burial in little-known African kingdom mystifies archaeologists

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

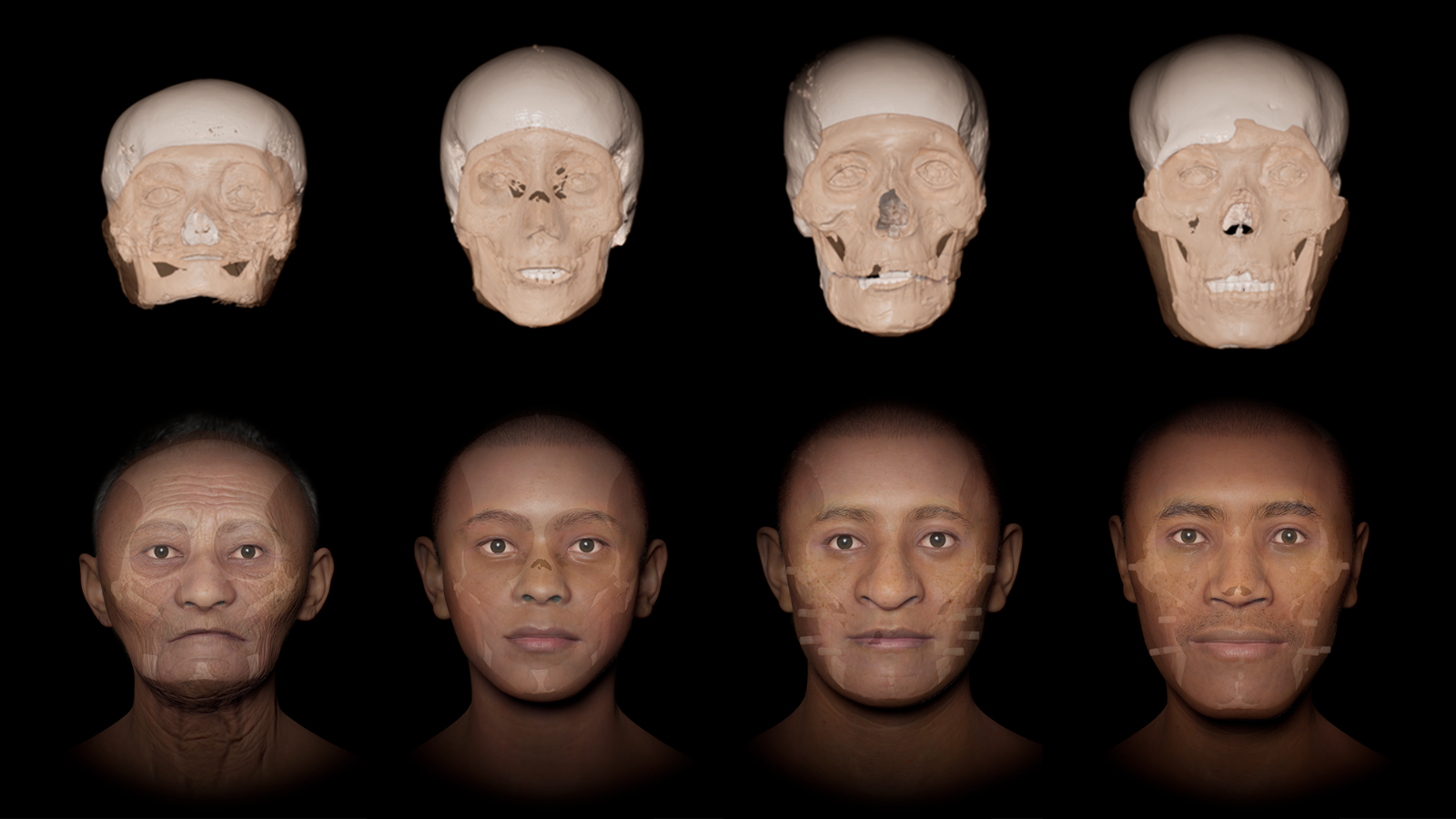

Scientists have digitally removed the 'death masks' from four Colombian mummies, revealing their faces for the first time

Scientists have digitally removed the 'death masks' from four Colombian mummies, revealing their faces for the first time

'Hot knives and brute force': King Tut's mummy was decapitated and dismembered after its historic discovery. Then, the researchers covered it up.

'Hot knives and brute force': King Tut's mummy was decapitated and dismembered after its historic discovery. Then, the researchers covered it up.

5,000-year-old skeleton masks and skull cups made from human bones discovered in China

Latest in Archaeology

5,000-year-old skeleton masks and skull cups made from human bones discovered in China

Latest in Archaeology

Diarrhea and stomachaches plagued Roman soldiers stationed at Hadrian's Wall, discovery of microscopic parasites finds

Diarrhea and stomachaches plagued Roman soldiers stationed at Hadrian's Wall, discovery of microscopic parasites finds

Oldest known evidence of father-daughter incest found in 3,700-year-old bones in Italy

Oldest known evidence of father-daughter incest found in 3,700-year-old bones in Italy

Rare 1,300-year-old medallion decorated with menorahs found near Jerusalem's Temple Mount

Rare 1,300-year-old medallion decorated with menorahs found near Jerusalem's Temple Mount

Detectorists find Anglo-Saxon treasure hoard that may have been part of a 'ritual killing'

Detectorists find Anglo-Saxon treasure hoard that may have been part of a 'ritual killing'

Ancient Egyptian valley temple excavated — and it's connected to a massive upper temple dedicated to the sun god, Ra

Ancient Egyptian valley temple excavated — and it's connected to a massive upper temple dedicated to the sun god, Ra

5,000-year-old dog skeleton and dagger buried together in Swedish bog hint at mysterious Stone Age ritual

Latest in News

5,000-year-old dog skeleton and dagger buried together in Swedish bog hint at mysterious Stone Age ritual

Latest in News

Scientists build 'most accurate' quantum computing chip ever thanks to new silicon-based computing architecture

Scientists build 'most accurate' quantum computing chip ever thanks to new silicon-based computing architecture

Japan laser weapon trial, comet 3I/ATLAS bids farewell, and AI solves 'impossible' math problems

Japan laser weapon trial, comet 3I/ATLAS bids farewell, and AI solves 'impossible' math problems

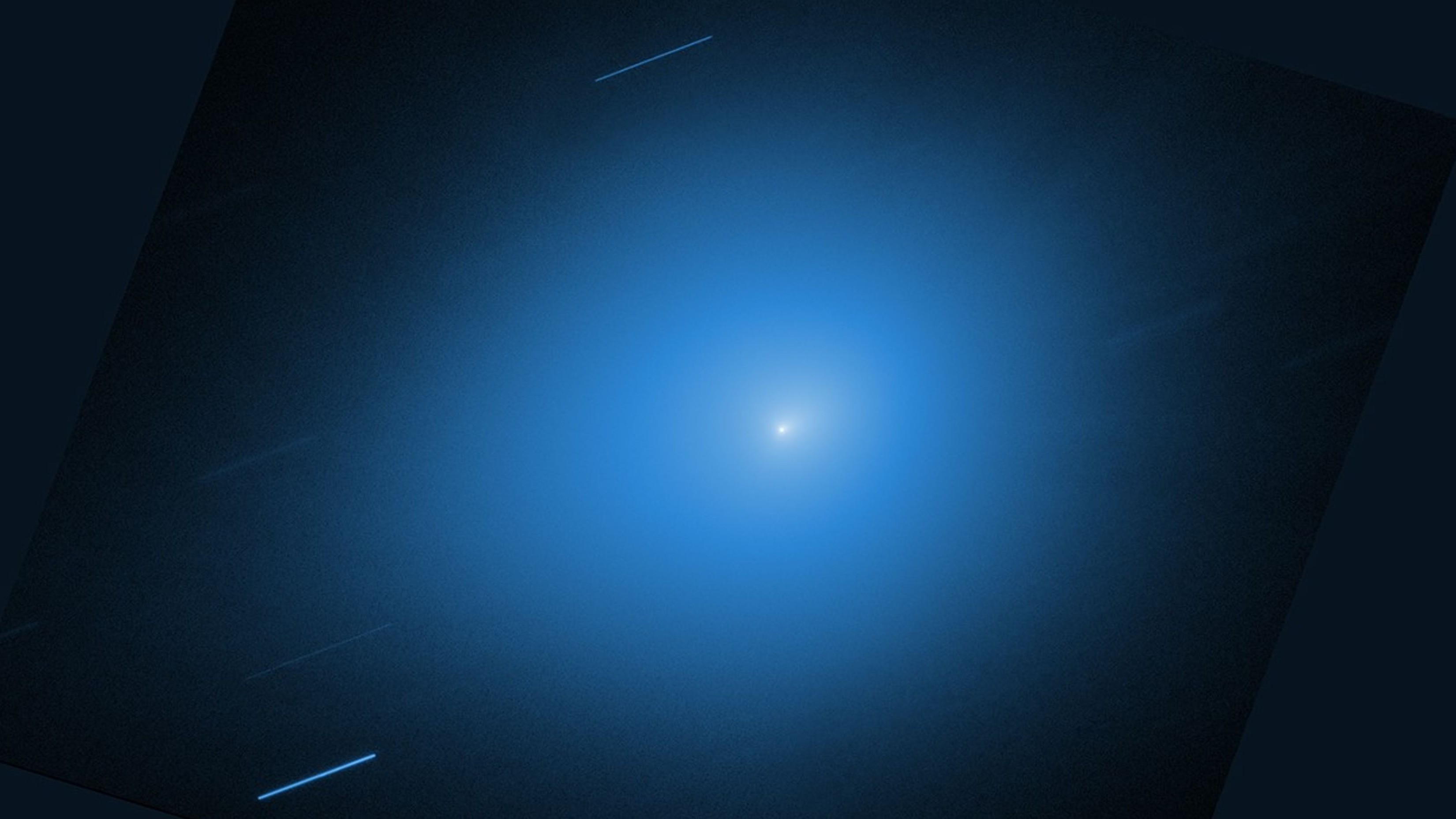

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS makes closest pass of Earth. Where's it heading next?

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS makes closest pass of Earth. Where's it heading next?

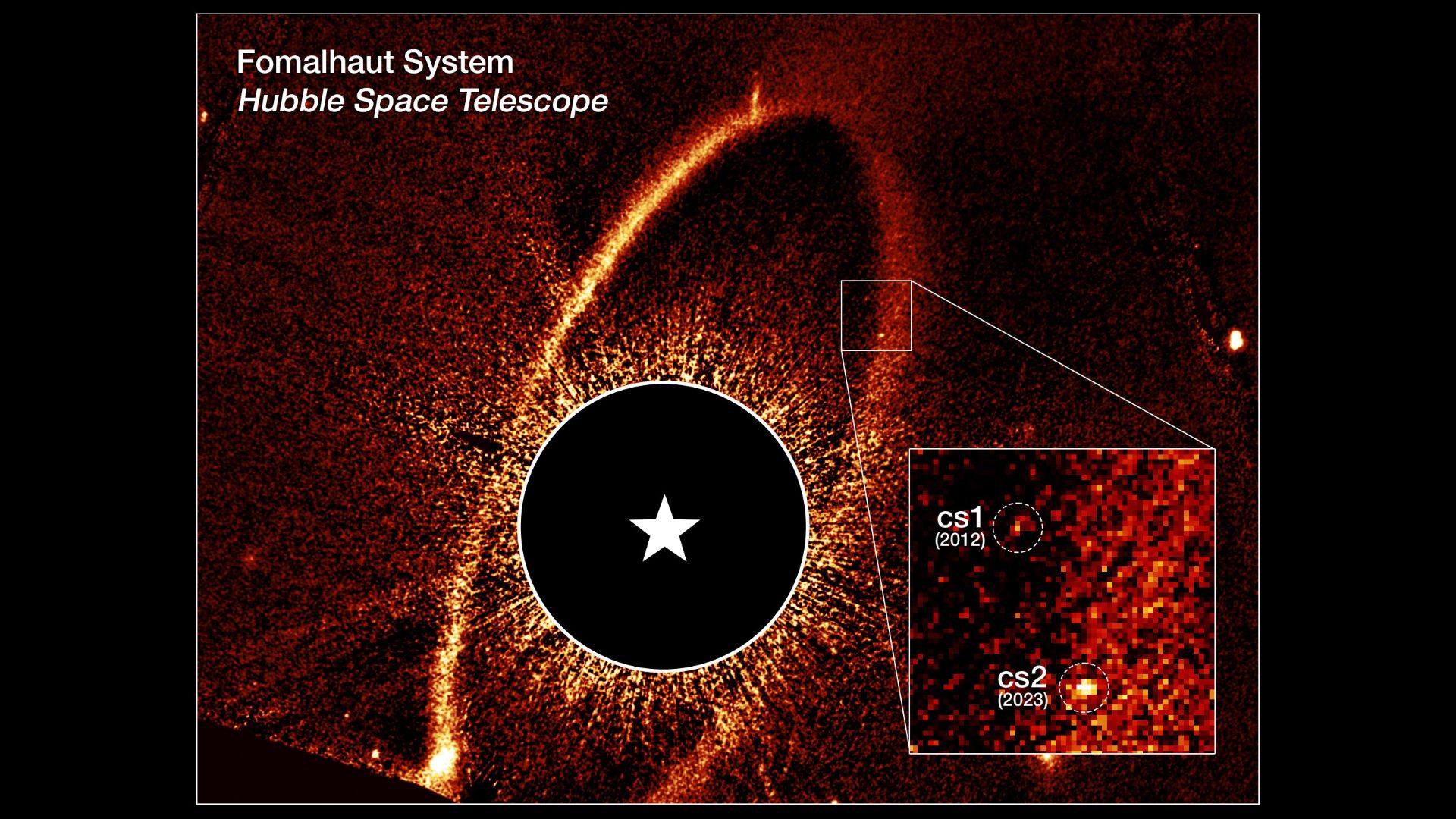

'Unprecedented' protoplanet collision spotted in 'Eye of Sauron' star system just 25 light-years from Earth

'Unprecedented' protoplanet collision spotted in 'Eye of Sauron' star system just 25 light-years from Earth

Comet 3I/ATLAS reaches its closest point to Earth tonight: How to see it

Comet 3I/ATLAS reaches its closest point to Earth tonight: How to see it

1,400 years ago, Nubians tattooed their toddlers. Archaeologists are trying to figure out why.

LATEST ARTICLES

1,400 years ago, Nubians tattooed their toddlers. Archaeologists are trying to figure out why.

LATEST ARTICLES 1The self-gifter's Christmas: Treat yourself to gear you'll actually want this Christmas

1The self-gifter's Christmas: Treat yourself to gear you'll actually want this Christmas- 2Glittering new James Webb telescope image shows an 'intricate web of chaos' — Space photo of the week

- 3Why is Venus so bright?

- 4Celestron Showdown: Battle of the 10x42s

- 5Science news this week: Japan laser weapon trial, comet 3I/ATLAS bids farewell, and AI solves 'impossible' math problems